Police Assisted Referral (PAR) Strategy Keeping Cleveland Safer.

Crime preventers have a new tool to help fight violations in the Cleveland community. The Cuyahoga County Metropolitan Housing Authority Police Department has introduced its Police Assisted Referral program, an initiative unlike anything else in the country.

PAR is a partnership among law enforcement, university crime prevention, the public housing community and mental health services that aims to identify potential violent crime early on by helping people with counseling and other services.

The program is a new and permanent way of policing where CMHA officers responding to violence-related service calls are trained to identify eligible individuals and families in need of these services, explained CMHA Chief of Police Andres Gonzalez. Police respond to roughly one thousand calls that deal with domestic violence in the household — violence that children witness. By providing help early, it is hoped that violent crime will be reduced.

“The program addresses what officers do 80 percent of the time and gives them a tool on the duty belt to address it,” said Dr. Mark Singer, professor of social work at the Case Western Reserve University Mandel School of Applied Sciences. “Officers are the first social responders. They work in communities and neighborhoods, and are the first to recognize a social problem.” These problems are domestic violence, delinquent or truant children, and alcohol and drug addiction.

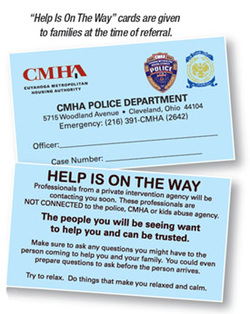

With PAR, officers are trained focused on three major points: recognize; identify; refer. At the time of a service call, the officer calls a referral directly into a FrontLine Services central intake center and provides the family with a referral card containing the responding officer’s information on the front and the referral number on the back. The officers clearly explain to residents that FrontLine staff members are not affiliated with the police and it is up to the residents to follow through. Once the call is placed, FrontLine responds to the family within 48 hours to schedule counseling either by phone or in person. Within 48-72 hours, an evaluation visit can take place at the residence or where the family members feel comfortable. From there, counselor and the family can assess if additional help is needed. FrontLine then send the officer a letter thanking the police for the referral, a copy of which is sent to the chief.

It has been proven that when these issues are addressed early, the sooner they can come to their conclusion, Singer explained. The focus is to help the children and the youth in the community. Helping the adults also directly helps the children. “There is no program like this in the United States,” said Singer, adding that they want to make it a national model for other cities in the US to follow.

To date, the PAR program is very successful and has received positive response. Three hundred families are actively engaged in PAR. Of those, 98 percent have decided to change and continue utilizing services, said Gonzalez. The majority of these referrals are the result of domestic violence situations. Citizens’ responses have been positive. Those who are referred to MHS by officers express appreciation.

Officers enthusiastically support it as well because they get into policing to help people in the first place and this puts officers in a positive light while providing some piece of mind. “It’s frustrating when you can’t help someone,” said Officer Robert Weiss of the CMHA Community Policing Unit, explaining that prior to the program, all the officers could offer was some off-the-cuff advice. Now officers are trained to handle referrals to mental health professionals. “We can walk away knowing they’ll get help instead of knowing we’ll have to go back later…based on the statistics, you don’t see reoccurrences at the same households (with this program) as often as you might (without the program).”

“The officers view it as a benefit to them knowing that they can help instead of being stuck,” said Weiss, explaining that the stress builds up and it helps to have a tool that helps take some of the stress away.

Weiss related a particular incident where a resident was having difficulty with her son. He was agitated and hitting things. The officer came out and spoke with them. The son had some mental health issues. The mother wanted assistance and the officer put in the call to MHS. The referral was actually made while they were standing there, and the mother was appreciative of the assistance. “There was no crime taking place,” said Weiss. “The son was just acting out. The mother needed more help.”

“Many people believe that officers spend most of their time making arrests or in negative interactions with citizens,” said Weiss. In fact, arrest situations take up 20 percent of the officer’s time or less, and 80 percent of those arrested are non-CMHA residents who victimize residents. The program improves the community’s perception of police.

The program, which went into effect in December, is the result of 10 years of planning. “Mike Walker [executive director of Partnership for a Safer Cleveland and STANCE (Standing Together Against Neighborhood Crime Everyday)] and I have talked about this for a least a decade,” said Singer. Originally, 35 officers were trained for PAR, but the program has been so impressive many more have been trained. The training, which focused on crisis intervention and problem recognition, was December 9 and 10; officers began referring December 11.

“The officers took that program and ran with it,” said Weiss, adding that they do not view it as more work. “The officers wish they could get more training.”

“This program is really a partnership,” said Walker. “This partnership has gone beyond our wildest dreams.” Partners include the CMHA Police Department, Case Western Reserve University’s Begun Center on Violence Prevention Research and Education at Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences, the Partnership for a Safer Cleveland, FrontLine., and most recently, Beech Brook.

“I think the program works,” said Weiss. “We’ve had residents tell us about how the program has helped them.”

“I’m committed to this,” said Gonzalez, explaining that whether or not funding is available, the program is a permanent change in policing practices – a new way of policing all together. “Regardless of what happens PAR is how we’re going to police.”